Flores Indonesia; History, Ethnic and Languages

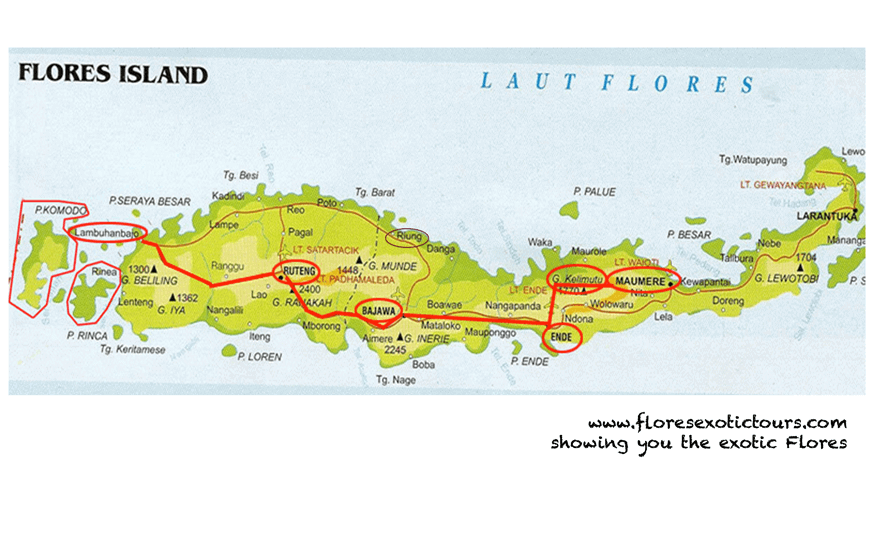

Flores is part of Indonesia’s Eastern Islands. It stretches snakelike between the longitudes of 118°–125° E, and between the latitudes of 8°–11° S.

The fascinating, strikingly beautiful island is blessed with plenty of natural attractions. There are white sandy beaches and deserted islands, soft-shaped hilly landscapes with beautiful rice field vistas, interspersed with mountainous areas. The island’s distinct rugged landscape with its complex V-shaped valleys and knife-edged ridges was formed by an impressive, young volcanic mountain range which spans over its approximately 400km length. Fourteen of the volcanoes are still active; others, like famous Mount Kelimutu in the Ende district, are extinct but nonetheless impressive with their crater lakes and calderas. Until not so long ago, this challenging terrain was hardly penetrable – a fact that contributed to the preservation of Flores’ extraordinary cultural diversity.

Flores can be visited all year around. Be aware, though, that the access to some of the mainland attractions during the rainy season (December – February) may be quite challenging or even impossible. Due to elevated sea levels, diving may also be restricted to certain sites.

In Flores, you will find plenty of beaches. Black, white and even pink sandy beaches, blue pebble beaches, beaches with mountains in the background, or just the jungle behind. Those untouched, beautiful coastal strips with a crystal-clear water are spread all around the island. Besides the beaches, there are several small islands which are great places to relax in idyllic surroundings.

Around Labuan Bajo, West Flores, are the secluded islands of Kanawa, Seraya Kecil, and Bidadari. They can be easily reached by one of the local excursion boats or by a chartered fishing boat. All of these islands are blessed with white sandy beaches and turquoise water. Take a swim, snorkel or lay back and just enjoy your pristine hideaway.

Around Maumere (East Flores), there plenty of easily accessible islands. The chain of islands includes, among others, Besar (‘Big’ in Indonesian), Babi (‘Pig’ in Indonesian), Pangabatang, Sukun, Palu’e, Pemana Besar and Pemana Kecil. Due to the small distances, chartering a boat and hopping around the islands is the best option for exploring all the idyllic beaches.

Before you dip into any of these tropical waters, reassure yourself that they are free of strong currents, and pay attention to tidal changes. Please be aware that – except for the islands that are frequently visited by tourists – it is considered inappropriate for women to wear just a bikini. If you do not want to attract too much attention, it is highly recommended to wear a t-shirt and shorts for swimming.

Forest

Flores is abounding with great forests. They range from lush, green mangrove forests in a healthy coastal ecosystem and bamboo forests (around Bena Village) to vast areas of tropical rain forests.

Mbeliling Forest in the West Manggarai district consists of two types of tropical rain forest ecosystems and is rich in limited-range bird life and endemic bird species. Furthermore, it serves as a critical watershed area for nearly 33,000 people who live in the area.

Besides Mbeliling, which offers great hiking opportunities, there are several other tropical forests that may be explored on foot, e.g. the mountainous forest of Mount Ndeki, the isolated mountainous scenery of Wae Rebo Village (both in the Manggarai district), or the forests of Kelimutu National Park (Ende District).

Mount Ndeki is one of the best places to observe tropical species of birds while wandering in the pristine wilderness of the mountainous forest. The forest is also home to green vipers camouflaging themselves as dry branches.

Most of the forests can be perfectly combined with a cultural visit to the nearby villages; for example, to visit the village of Wae Rebo, there is a pleasant hike through a dense rain forest along a narrow path to reach the village. This forest is one of the biologically richest areas in Indonesia.

The surroundings of the Kelimutu crater lake, belonging to the famous Kelimutu National Park offer lush forests full of birdsong. These forests are blessed with rare flora, such as pine, mountain fig, and redwood.

The current geological formations found in Flores and throughout Indonesia were predominantly shaped by dynamic geological transformations during the early Pleistocene period (1.8 million years ago). These transformations included significant tectonic movements with corresponding volcanic activities and extremely high sea-level fluctuations.

A craggy mountainous landscape reflects the island’s turbulent geological history in the midst of the so-called ‘Ring of Fire’, a geologically unstable hot-spot. Flores is part of a volcanic belt which stretches from Sumatra through Java and Bali to the Banda Sea. The island’s highest, still active volcanoes are Mount Egon (1703m) in Maumere and Mount Inerie (2245m) in the Ngada district. However, the most famous volcano is Kelimutu with its tri-colored crater lakes, shimmering in green, turquoise, and black-red. Although many of the volcanoes in Flores are not classified as active, they display a number of post-volcanic formations worth seeing, such as calderas, basalt columns, and volcanic lakes.

The volcanic activity is strongly linked to the island’s position in a subduction zone, which is a tectonically active spot where a number of different tectonic plates – the Eurasian, Pacific, Indian-Australian, and Philippino plates – collide. There, the heavier oceanic plate sinks under the lighter continental plate, where they melt in the heat of a layer of liquid asthenosphere. The emerging pressure, friction, and melting processes at the edge of these plates often cause volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, and tsunamis. Flores is very prone to these natural powers that sometimes cause major disasters: in 1992, a strong earthquake, followed by a massive tidal wave, claimed the lives of 3,000 people and destroyed the town of Maumere and its surroundings.

History

Since very early times, the Florinese have been confronted with people from many parts of the world. Some of them came with purely economic intentions, others with ideas of power and belief. Whatever their interest in Flores might have been, it is certain that these outside influences left their footprints and contributed to the already manifold social and cultural diversity.

Flores has had its own history long before the first traders or missionaries arrived. However, as ancient Florinese societies shared their history through oral tradition, little is known about the origins of many of them. The first foreign visitors to Flores probably encountered dispersed, independent settlements consisting of several lineages which descended from a common ancestor. By that time, political authority was locally limited.

Before the first Europeans reached Flores, Makassarese and Bugis seafarers from Southern Sulawesi came to Flores for trading and slave raiding and took control of some of the coastal areas. While the eastern coastal areas of Flores were under the authority of the emperors of Ternate in the Moluccas, West Flores was prominently ruled by the sultanates of Bima in Sumbawa and Goa in Sulawesi.

Colonial era

A Portuguese expedition crew reached the island in the early 16th century and named it ‘Cabo das Flores’, which means ‘Cape of Flowers’. The island became an important strategic point for the economic activities of Portuguese traders. However, Flores itself was neither a source of valuable spices nor sandalwood. After a long period of struggling with other trade powers, the Portuguese were finally defeated and withdrew themselves to Dili in East Timor in 1769. They renounced all their spheres of influence in Eastern Indonesia and sold their remaining enclaves on Flores to the Dutch administration.

Even though the Dutch administration was eager to expand its influence in Indonesia, it hardly interfered in local political issues at the beginning. When the Dutch administration decided to increase Flores’ potential as a source of income for its state treasury, systematic measures were taken to improve the island’s infrastructure and educational system. Being increasingly challenged with rebellions and inter-tribal wars, the Dutch army launched a massive military campaign in 1907 to settle the disputes. After being subdued in 1909, the island was provided with a new administrative system, dividing it into the five major districts of Manggarai, Ngada, Ende, Sikka, and Flores Timur. Each of these administrative units was headed by a local leader who was appointed by the Dutch colonial government.

Except for a short period of Japanese occupation during World War II, the Dutch remained the dominating colonial force until Indonesia became an independent nation-state in 1945.

Nation building

The main focus of Indonesia’s first president, Soekarno, was the building of a national identity for the new-born state and the preservation of its fragile unity. Soekarno and Hatta proclaimed Indonesian independence on 17th August 1945. After four years of bitter armed struggle and international pressure, the Netherlands formally recognized Indonesian independence. On 17th August 1945, Soekarno proclaimed a single unitary Republic of Indonesia. He also elaborated the idea of Pancasila, Indonesia’s five pillars of national unity, as an attempt to incorporate the many different religious and ethnic groups into an independent nation-state.

President Soeharto, who followed Soekarno after a period of violent takeover in 1965, aimed to lead Indonesia from its rural condition into the modern industrialized world. An important political issue under his so-called New Order government was the economic development and growth of Indonesia. Therefore, the government launched many health care, education, economy, and infrastructure programs and projects with the idea of bringing modernity to the remotest villages. After a long period of governing Indonesia in a rather authoritarian way, President Soeharto was brought to fall in 1998.

Flores today

After the Soeharto regime, Indonesia was turning into a more democratic and decentralized state. The positive effects of these new policies for Flores were limited: the majority of the Florinese people could not directly benefit from the increased local autonomy and decentralization and remained to be among the poorest inhabitants of Indonesia. Most families on Flores still struggle with the educational system. They cannot afford to pay the school fees for their children, thereby reducing their future opportunities to make a living beyond rural agriculture. Besides, access to health care is very limited – not only in the remote villages but also in the larger towns. Furthermore, access to water, electricity, transportation, communication, and information is still at a low coverage level.

However, the policy shift from a centralized focus on Javanese culture to an increased appreciation of Indonesia’s rich local cultural varieties brought some positive change: traditional cultural features and peculiarities are not equated with backwardness anymore, but proudly valued as the country’s treasure and heritage, which also has the potential to attract domestic and foreign tourists – and their spending power.

People and culture

To talk about one single Florinese culture would definitely not live up to the stunning variety that visitors find in Flores: unique local expressions of livelihood, ethnicity, language, origin, belief systems, social structures, and history that found their way through history into the present.

Flores’ amazing cultural diversity can be partly explained by its geographical attributes, partly also due to outside influences. However diverse, Florinese societies still share many common cultural and linguistic traits within and beyond their island.

Language & Ethics

The uniqueness of Flores lies in its amazing wealth of cultures, languages, and history. One of the explanations for these local varieties lies in the island’s mountainous nature: it hindered the access to the interior areas and made communication between individual communities difficult, thus preserving a huge range of long-standing local peculiarities.

Flores is inhabited by 1.8 million people who roughly belong to the major ethnolinguistic entities of Manggarai, Ngada, Nagekeo, Ende and Lio, Sikka and Lamaholot. These groups can be further divided into many sub-entities with their own cultural features and dialects.

Indonesian (Bahasa Indonesia), the official language, is used in the context of education, business, and formal affairs. However, everyday conversations in Flores are still carried out in the countless local languages and dialects, which all belong to the so-called Austro-Polynesian language family.

Lamaholot

The Lamaholot people live in Eastern Flores in an area reaching from the mainland of the Flores Timur district to the islands of Solor, Adonara, and Lembata. Lamaholot is more of a language than an ethnic group. The linguistic boundaries do not exactly correspond to the political borders, and the Lamaholot people do not consider themselves to be a cultural unity. However, the name ‘Lamaholot’ has been recently applied to the ethnic group as they share many common cultural elements – e.g. the widespread practice of the use of elephant tusks as a part of marriage prestige.

Another widely shared element of Lamaholot culture used to be its distinct system of ritual leadership, where four ritual leaders also shared governing power: the kepala koten (kepala means ‘head’ in Indonesian) was in control of internal village affairs. The kepala kelen took care of external affairs. The other two positions, hurit (also hurin or hurint ) and marang, had advisory functions, while other influential village elders ensured that none of these leaders got too powerful.

As is commonplace in many parts of Eastern Indonesia, the Lamaholot people also used to recognize a double-gendered divine being, consisting of ‘Lera Wulan’ (sun-moon) and its female complement, ‘Tana Ekan’. Nowadays, the male Lera Wulan is associated with the Christian or Muslim notion of God. According to the traditional Lamaholot belief system, lesser spirits, called nitu, inhabit treetops, large stones, springs, and holes in the ground. Also worthy of mention are Ile Woka, the god of the mountains, and Hari Botan, the god of the sea.

Besides prominent ceremonies and festivals associated with house building, agricultural happenings, and other events, the Lamaholot people also hold celebrations on the beach in connection with the beginning of the annual fishing cycle.

The Sikkanese people live in the Sikka district in East-central Flores. They are famed for their fine ikat weaving, a handicraft deeply rooted in Sikkanese society, which is still of high economic and social importance. Producing probably the finest ikat in Flores, it is a pleasure to see so many people wearing the beautiful traditional sarongs in their daily lives. Besides the art of ikat weaving, the district boasts a fascinating history of their ancient kingdom and the integration of early outside influences into their local culture.

The Tana ‘Ai and the Sikka-Krowe

The two major societies of this district are the Tana ‘Ai people in the mountainous eastern part of the district and the Sikka-Krowe people in the central areas, as well as on the north and south coasts. Sikka is the name of the ethnic group as well as the domain formerly ruled by the King of Sikka. Apart from speaking different languages, the Sikka-Krowe and the Tana ‘Ai societies also have some cultural differences.

Due to their isolated settlements, the Tana ‘Ai were not exposed a lot to outside influence until recently. They used to live in several loosely organized domains called tana. These domains were less territorial entities, but more defined by religious and ceremonial borders. Each tana was led by the head of the domain’s founding clan, and also had its own mahé, a central ceremonial site which was found either in the village center or at a place in the surrounding forests. Unlike many (other) Florinese societies, the Tana ‘Ai never had their own kingdom, nor did they have a prominent bride-wealth system. Another distinctive feature of the Tana ‘Ai is their complex and elaborate ritual language.

In contrast, the Sikka-Krowe were frequently exposed to foreign encounters, including the Portuguese at the beginning of the 17th century, who left cultural footprints that are still noticeable. The Sikka-Krowe turned into a small kingdom, with the village of Sikka Natar on the south coast as its center of power.

The first king to rule Sikka at the beginning of the 17th century was Mo’ang (or Don) Alésu Ximenes da Silva. During the Portuguese era in Eastern Flores, the people of Sikka Natar took on Portuguese names, with the name ‘da Silva’ referring to the members of the ruling house. A myth dates the origin of this ruling house to a time way before the arrival of the Portuguese. The story tells about people from South Asia who were shipwrecked on the southern coast of Flores near today’s Sikka Natar. As they could not repair their ship, they decided to settle there. Soon they started to arrange marriage alliances with the indigenous people who lived in the hilly interior. Don Alésu is believed to be a descendant of these shipwrecked wayfarers. The myth also tells that the young Don Alesu traveled to Malaka where he studied political science and got acquainted with a Christian religion. When he returned to Sikka, he brought with him Catholicism and founded the Kingdom of Sikka.

After Don Alésu, Sikka was under the subsequent rule of seventeen of his descendants. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the Dutch transformed it into a semi-autonomous state, based on a policy of self-rule. The small kingdom had its heyday right after the Dutch withdrawal post World War II. With the passing of the last king, Don Josephus Thomas Ximenes da Silva in 1952, the rule of the royal house of Sikka came to an end. Even though the kingdom had to give way to the young Indonesian nation-state, it lived on in the memory of the Sikkanese people as a prominent element of their cultural history.

The festive Lio people live in the Ende district of Central Flores, where they make up the ethnic majority. The Lionese people use a fascinating range of artwork – architecture, carving, ikat weaving, jewelry, and more – which bursts with symbols that tell about their history, social life, and cultural values. Some of the most prominent motifs in Lionese culture are boats, snakes, horses, and humans. With natural attractions like the world-famous Kelimutu crater lakes, the Lio area is a hiker’s paradise and worth at least a couple of days of exploring.

The influence of adat belief systems is still quite strong in the Lio area. This may be explained by the fact that most of the Lionese people settled in mountainous terrain, therefore never gave up dry-rice farming. Consequently, many rituals and ceremonial activities related to the agricultural cycle of dry rice are still considered important, be it at the time of starting a new dry-rice field, the planting, or harvesting.

A characteristic of many Florinese cultures, the traditional Lionese belief system, is also centered around the notion of the highest divine being that unites opposites, called du’a gheta lulu wula, nggae ghale wena tana – the old one up on the Moon, the ruler on Earth. The Lionese people believe in an afterlife. Therefore, the dead are buried with gifts to take to their afterlife. Good and bad spirits, as well as magic practices, are other important elements of the traditional belief system. Many of these ideas and practices live on, quite smoothly paralleled by Catholicism and Islam.

The Lionese people used to have and still have a distinct political system dominated by the mosalaki – leadership personalities with different responsibilities. At the very top of the hierarchy stands the ria bewa, or the ‘great long one’. As he has an all-encompassing decisive power, he may be called the highest authority of a Lionese village. The ria bewa is followed by the mosalaki pu’u, the ‘first mosalaki’, who takes the role of the ria bewa’s executive and assistant in ritual matters. If, for example, the ria bewa decides that measures have to be taken to bring rain, the mosalaki pu’u will ensure that the necessary rituals will be arranged and performed properly. Depending on the size of a community, there is a number of additional mosalaki, each with his own specific responsibilities.

Ngada Nagekeo

Visitors to Flores who are eager to encounter an extraordinarily vivid traditional material and ideal culture should take some time to meet the Ngada (or Ngadha) and the Nagekeo people. These fascinating communities live in Kabupaten Ngada and Kabupaten Nagekeo, the same-named districts in Central Flores. The Ngada people prominently settled around the legendary Mount Inerie and the district’s capital town, Bajawa. The Nagekeo people settled around the district’s capital town, Mbay. Apart from the Ngada and the Nagekeo communities, who represent the major socio-cultural units, the districts are home to several minor ethnolinguistic groups.

Even though the icons of Ngada culture – eye-catching ancestral shrines, impressive megalithic formations, distinct architecture, and a vivid ceremonial life are testimonies to a distant past; they are not just relics, but an integral part of the Ngada people’s present, which is a syncretistic co-existence of ancient belief systems and Catholicism.

In contrast to other Florinese societies and the Nagekeo people whose social organization is based on patri-linearity, the Ngada people determine their clan belonging through their maternal line. Genealogical continuity is transmitted only through women, and the children are regarded as members of their mother’s clan. Land rights, material inheritance, and residence are passed on matrilineally as well. However, Ngada matrilineal structure does not mean that women have all the decisive power in a community’s daily life. It is the men who usually dominate the public sphere, gatherings, and political or legal debates. In the private realm, though, it is the women who take prominent decisive roles.

In their local language, the Ngada people refer to their village as nua. A nua consists of several houses which are owned by different clans. The houses are usually set up along two parallel lines. Each clan owns a pair of ancestral shrines, Ngadhu and Bhaga, which are situated in the center of the Nua. Next, to the shrines, arrangements of megaliths are another famous element of Ngada material culture.

The most popular villages in the Ngada district are Bena and Wogo. Both have become signposts of Ngada culture and display the richness of Ngada traditions. However, there are many other villages off the beaten track which are worth a visit.

The Manggaraian people are famed for their long-standing heritage of ritual and ceremonial life, as well as distinct agricultural and architectural practices. Caci performances, Lingko fields, and the Penti ceremony are just a few among many highlights that the Manggaraian people are proud of. With its many myth-spun cultural sites, embedded in beautiful natural surroundings, Manggarai offers treasures not to be missed during a trip to Flores.

Manggarai, situated in the westernmost part of Flores, is the island’s most densely populated region. It is divided into the three Kabupaten (administrative districts) of Manggarai Barat in the West, Manggarai in the center, and Manggarai Timur in the East. Manggarai is considered to be roughly an ethnolinguistic unit. However, there are many different dialects of the Manggaraian language as well as some local variations of cultural elements.

Very little is known of the earliest history of the Manggaraian people. This gives way to colorful myths and stories about their origin and descent. Many Manggaraian people believe that their ancestors came from Minangkabau in West Sumatra, settled on the coast, then proceeded to the island’s interior.

A central theme of Manggaraian culture is the unity of the village, the house, and the fields, which is most visibly expressed in their circular shape and their spatial division into segments. A house used to be much more than a shelter to its inhabitants, rather an expression of identity and belonging: the particular architecture and structure symbolized kinship and marriage relations, as well as patrilineal descent. Before the Dutch colonial administration put an end to this way of living, entire clans used to inhabit a single house, with different generations living side by side.